On Jaywalking

I was rereading the Crito today, and I realised that the argument Socrates makes in this dialogue is one that is rarely taken seriously. Since everything that Socrates says is true (we must remember first principles), this is a problem. The argument from the Crito is that it is always unjust to harm the laws of one's country by breaking them, since one has made an agreement to follow those laws by living there. Therefore, even though Socrates did not in fact corrupt the youth, he was convicted by due proceess and it would be unjust for him to escape from prison. Socrates believed so strongly that one ought not to break the laws of one's country, that he allowed himself to be executed.

I was rereading the Crito today, and I realised that the argument Socrates makes in this dialogue is one that is rarely taken seriously. Since everything that Socrates says is true (we must remember first principles), this is a problem. The argument from the Crito is that it is always unjust to harm the laws of one's country by breaking them, since one has made an agreement to follow those laws by living there. Therefore, even though Socrates did not in fact corrupt the youth, he was convicted by due proceess and it would be unjust for him to escape from prison. Socrates believed so strongly that one ought not to break the laws of one's country, that he allowed himself to be executed.I compared this with our current approach to law. We usually don't agree in extreme cases like Socrates' that we ought to follow the law. Take the end of the film The Shawshank Redemption, for example. The situation in this film was similar to Socrates' situation: a man unjustly convicted has the opportunity to escape. Yet, in this film, we are cheering for the escapee. We do not even hold to Socrates' principle in trivial situations. Looking outside the window of the library here, I can see at least two people jaywalking. I jaywalk myself constantly. Rather than travel an extra half block to a streetlight, we will illegally run across the street. We are therefore unwilling to put in even a few seconds of effort to avoid doing what Socrates was willing to die rather than do.

I would suggest that our willingness to do willy-nilly what was a matter of life or death for Socrates is a result of our fears of unjust laws and that an absolute requirement to follow the prescriptions of law would require us to behave unjustly. Since we don't believe in an absolute duty to follow the law, we do not feel any obligation even (or perhaps especially) in trivial matters. However, I will examine two positions, by Saint Thomas Aquinas and Martin Luther King that seek to reconcile the absolute prohibition against breaking the law with an absolute prohibition to do injustice even when the law commands it. Both of them took being law-abiding very seriously.

Aquinas's argument stems from his belief that there are different strata of law. These strata are the eternal law (the will of God), the natural law (what leads to the natural good) and the positive law (laws promulgated by states). These laws are not "higher laws" that trump "lower laws", as though they are somehow in conflict. Rather, an analogy can be seen in a regimen prescribed by a doctor. The art of medicine is applied in a particular case to create a regimen for a given patient. So too the natural law is applied in a particular case to create a positive law for a given state. The positive law cannot be in conflict with the natural law, any more than a particular regimen can be in conflict with the art of medicine. Therefore, an apparent positive law that violates the natural law is not really a law, for the same reason that a regimen that does not aim at health is not really a regimen. As a result, any law that commands us to do something contrary to the natural law, such as murder people, is not really a positive law and can be disobeyed in good conscience.

King's argument is quite different, but he takes obedience to the law very seriously as well. In the "Letter from Birmingham Jail", he explains how civil disobedience is not, in fact, breaking the law. Law is not simply a command not to do something; it has a penalty attached. If it were simply a command, it would just be advice. Therefore, laws are not commands but conditional statements: "If you do x, then you will suffer penalty y". As a result, he argued, one is not breaking the law, if one is willing to accept the penalty accorded to the action by law. Nor is it enough to be willing to suffer the penalty if caught. One must openly commit the action so that the state may decide what to do. In time, if enough good people are willing to go to jail as a result of unjust laws, it will shame the state into change.

How, then should one apply this to a case like jaywalking? In Aquinas's model, a positive law is a real positive law so long as it does not violate the natural law. Therefore, unless a law is commanding us to do something unjust, like turn over our children to be sacrificed, it is a real positive law. Laws that are silly, like a prohibition on drinking or green hats, are real laws and must be obeyed. Further, jaywalking laws are not silly, and most of us would admit. A complete free-for-all of pedestrians would be hazardous both to themselves and to cars. In King's model, we are breaking the law against jaywalking, as we are committing the action with the intention of not getting caught or paying a fine. This is not civil disobedience, but just lawlessness.

Socrates, Aquinas and King all has the utmost respect for the law. Socrates was willing to die rather than escape from prison after a legitimate sentence of death, and King repeatedly went to prison in order to shame lawmakers into changing the laws. Next time, when there is a crosswalk only a few feet away, perhaps all of us, myself included, ought to be more conscious of their example.

3 Comments:

How would you reconcile Socrates' claim in Crito that one must always obey the law with his claim in Apology that if the court ordered him to abandon philosophy, he would not obey?

It is my belief that our laws are not nearly so silly as is commonly though. Being a lawyer, I am obligated to point this out on a regular basis. This is common with copyright situations. We should start from the assumption that we are allowed to do any given act unless there is a law against it, i.e. the law does not enable, it prohibits. Working from this principle, since there is no law against it, nearly all of what we call "jaywalking" is legal in Ontario. There seems to be some limitations on when pedestrians can cross (e.g. you need to yield to the traffic when not in a cross-walk, and you cannot jump in front of traffic just because you are at a cross-walk) but these are commendable limits. As for the theoretical problem which Dan is raising (because Jaywalking is probably illegal in some places) I need some more time to read his article and think.

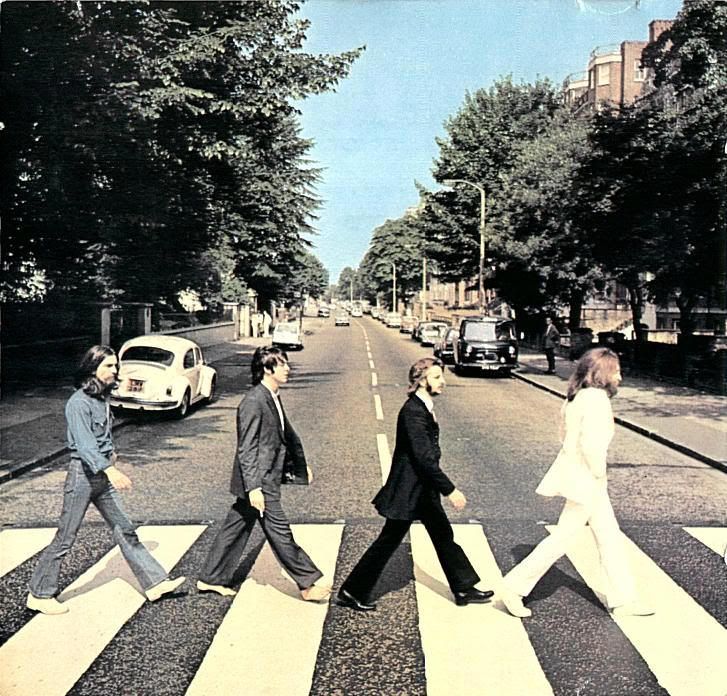

mmm.. the beatles.

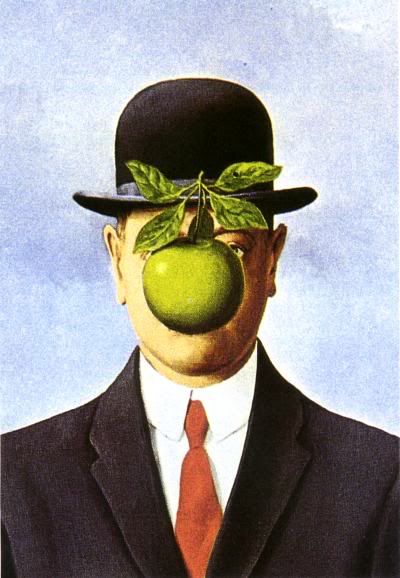

beautiful.

Post a Comment

<< Home