The Dangerous Mule

This essay is concerned with mules. No, really. It is about the sterile offspring of horses and donkeys. The "mule question" is a fascinating and queer puzzle that deeply worried Aristotle. It is also a problem that has been almost totally forgotten about since Darwin. Before Darwin, the mule presented the first real challenge to the Aristotelean doctrine of essences of biological organisms. Since Darwin, philosphers have mainly focussed on the challenge evolution presented. By looking at his response to the mule doctrine, one can see how Aristotle might have responded to Darwin had their millenia been reversed.

This essay is concerned with mules. No, really. It is about the sterile offspring of horses and donkeys. The "mule question" is a fascinating and queer puzzle that deeply worried Aristotle. It is also a problem that has been almost totally forgotten about since Darwin. Before Darwin, the mule presented the first real challenge to the Aristotelean doctrine of essences of biological organisms. Since Darwin, philosphers have mainly focussed on the challenge evolution presented. By looking at his response to the mule doctrine, one can see how Aristotle might have responded to Darwin had their millenia been reversed.Aristotle's biological theory was essentialist. Each species, including humanity, had an essence to it that didn't change over time. This was relevant to biology, as it tells us what we are looking for in biological research. It was the universal truth that could be inferred from the particular evidence. It was relevant to logic, since it told us what was properly considered a subject and what was properly considered a predicate. The Greek phrase to ti en einai, translated "essence", literally means "what it was to be". In other words, when you ask me "what I am", "human" is the truest, most specific answer I can give you. Finally, it was relevant to ethics, since each member of a species should be judged relative to the ideal capacities of a member of that species. For instance, a human being who cannot fly is not defective, but a sparrow that cannot fly is.

The mule was a threat to this conception of biology. Aristotle needed to establish a criterion according to which two organisms could be considered a part of the same species. An Ethiopian and a Greek are members of the same species, but a squirrel and a chipmunk are not. He settled on the criterion that has largely stuck in biology up to the present day, that of viable reproducibility. That is, you could recognise something as a member of a species, because it was able to make more of that species when mixed with another of its species.

This was not a completely arbitrary criterion. Aside from being the most obvious solution, Aristotle was concerned about where the essence of the baby animal would come from, that is, its formal cause. "Chipmunkness" had to get into a baby chipmunk somehow, so he believed that it would need to be from another chipmunk. Therefore, reproducibility and esssences worked hand-in-hand. Reproducibility explained where the baby's essence came from, and the natural division of essences could be discerned through reproducibility.

Enter the mule. The mule threatened to blow the whole system a part. (I have no evidence for this, but I believe Asimov was aware of this, which is why "the Mule" is a "mutant" who threatens the systematic predictions for Foundation). The mule was a sterile hybrid of a donkey and a horse. Aristotle was stuck. Donkeys and horses can't reproduce together viably, since their offspring are sterile. Therefore, donkeys and horses are different species. However, if donkeys and horses are different species, then which species is the mule? It clearly has horse parts and donkey parts, so it is not really just a horse or just a donkey. However, there cannot be a separate species of "mule" either, as they cannot reproduce at all, let alone viably. So, the mule is not essentially a horse or a donkey or a mule. Apparently the mule, then, has no essence, that is, it has no to ti en einai, since it is of no particular species.

This can't be right. The mule is walking around and braying, so it must have an essence. Aristotle had two solutions for this. His first solution doesn't work. He suggests that the mule may be an instance of the genus of which horses and donkeys are members, for our purposes, the genus equus. This creates a serious problem, though. One can say that a horse is essentially a "equus caballus" and a donkey is essentially a "equus asinus". It is the "caballus" and the "asinus" that provide the essence, though, and properly answer the question of "what it is". "Equus" is just a category according to which we group species. If a mule is just an "equus", full stop, it has no species and no essence. Worse, Aristotle is claiming that, even though it is not a member of any species it is still somehow a member of a group of species, which makes even less sense.

The second solution Aristotle gives is that the mule is just an exception to the normal regularity of nature. Aristotle occasionally does this, and it seems as though he is just throwing up his hands. However, it is an important part of Aristotle's methodology. He says that it is shameful (aischron) to treat a subject with more precision than it deserves. One should not expect a system to fit nature precisely. The mule is a case of that.

This tells us something very interesting about Aristotle sees his system of biological essences. He believes that his account is only an approximation and is willing to countenance exceptions. How, then, might he respond to Darwinian evolutionary theory? Since Darwin, many people have argued that Aristotelean essences and biology have been refuted. One of the main reasons this claim has been made is because Darwin claimed that the line between species is not sharp but blurry. However, Aristotle had already made room for the possibility of blurry interspecies lines. His doctrine of essences does not require that there be no blurring between the species, only that a discernible population that can reproduce viably exists. This is still true, and nothing about evolutionary biology shows otherwise. As such, Darwinian biology does not refute Aristotle's theory of essences.

The mule posed a great challenge to Aristotle's theory of biology. Fortunately, the problem of mules gave Aristotle the opportunity to wrestle with the fluidity of species that would not seriously resurface for over two thousand years. Because of this opportunity, it is possible to have some sense of how Aristotle might have responded to evolutionary biology.

18 Comments:

Could there be a case where, thousands of years down the line, horses are no longer able to reproduce with donkeys? Perhaps the mule is a case of evolution which is unfinished : the separation of one species into two, which is as yet incomplete. Since horses and donkeys rarely interbreed in the wild (indeed there exists but one extant breed of wild horse, the Przewalski horse) the debate is perhaps moot.

If you bring asexual reproduction into the fore, or species that reproduce leaving genetically identical offspring, you're in a lot more philosophical trouble. I am rather more satisfied by the definition [source Wikipedia] of biological separation "The key to defining a biological species is that there is no significant cross-flow of genetic material between the two populations."

Other species divisions have been defined by morphological factors or via other types of reasoning such as "when such a divergence becomes sufficiently clear, the two populations are regarded as separate species" [source Wikipedia, ibid.] but this begs the question: by which method you make sure that divergence is sufficiently clear. Which brings me back to genetics, to which sexual and asexual reproduction can ultimately be keyed.

Perhaps it's just easier to say that a mule is a non-viable donkey-horse gene hybrid.

I believe that the mule is a donkey. Consider this, is a dwarf another species?

errrr....I guess you just don't understand the concept of hybred.

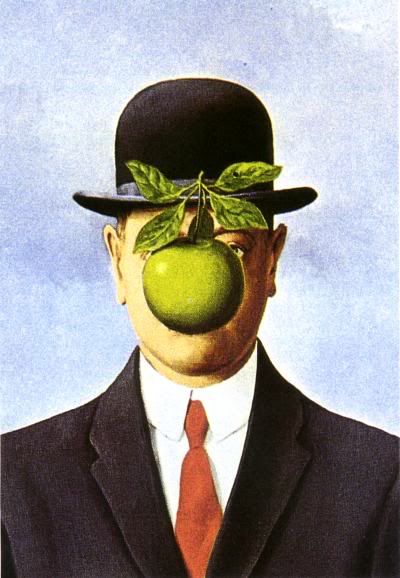

The pic looks like someone who once attended a family gathering of mine...

Thank you for the comments, all. Fruey, you're right to point out that asexual reproduction is problematic for Aristotle as well. I was just focussing on mules, because they're interesting.

If you're interested in some of Aristotle's biological puzzles, he has some fish that reproduce asexually, flies that generate spontaneously, and bees that have one sterile group (workers), one group that produces itself plus workers (kings) and one group that reproduces itself (drones). These are all found in Generation of Animals.

I once knew a Mule. His name was Chip.

Since I didn't have a horse, I rode the mule.

One day, he bucked me off.

Is a mule another word for Jackass our are they completly differnt?

I just really wanted to say jackass. I know the answer.

Nice blog. I would like to see UND republish Etienne Gilson's From Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again. It annoys me that it is out of print.

Surely Plato's stepchildren are welcome at the Lyceum.

Interesting post.

I can only wonder how far Aristotles could have gone with today's knowledge.

And i can't help but draw a connecting line between "essence" and DNA.

your Mule is a Zorse:

http://www.geocities.com/zedonknzorse/basics.html

Frank is right...your mule is a zorse... I don't know what Aristotle knew about it all, but the mule had lots of company...zorse, zedonk, hinny. Also, not all mules are sterile which would have really been a problem for Aristotle...what to do about offspring from hybrids, etc...

Fascinating.

This article is now completely torn apart. Last year (2007)a mule foal was born to a mule in Colorado. They have done DNA tests and it is indeed her own foal. Mules have been known before to have foals, but they were always thought to have been stolen from other horses. They have now found, through DNA testing, that mules can, indeed, reproduce. They are/can be a viable species.

One more thing. They do not bray. They do not neigh. They breigh. It is exactly a cross between the bray and the neigh, a kind of laughter.

Oh, and to answer the question about the jackass, a mule is actually half-assed. I always tell people my mule is not an ass, she is only half-assed.

It is only hinny's that can reproduce, but the chances are near to 1 in a million, no stallion mule has ever reproduced. If anyone knew what they were on about that at least know the difference between a hinny and a mule.

My question is, does anyone know the genetic facts as to why mules are sterile?

Actually a hinny is the offspring of a horse stallion and a donkey jennet, while a mule is the offspring of a donkey jack and a horse mare. If I recall correctly the only known genetically verified full-term foal born to one of these half-asses was actually born to a mule,not a hinny.

I am going to correct myself as I went and checked. There have been 60 verified cases of molly mules bearing young (actually 59 molly mules and 1 female hinny). There have never been any cases of fertile john mules (the males).

Mules and donkeys are not the same. A mule is half donkey and half horse. The reason mules are sterile is because they have an uneven number of chromosomes, 63 to be exact. Since 63 cannot be divided into two meiosis is impossible. Horses have 64 chromosomes and donkeys 62. The reason a mule can reproduce with a donkey is because a chromosome can be deleted. It's much easier to take out genetic material than to make it up. Hope this was some helpful insight.

Post a Comment

<< Home