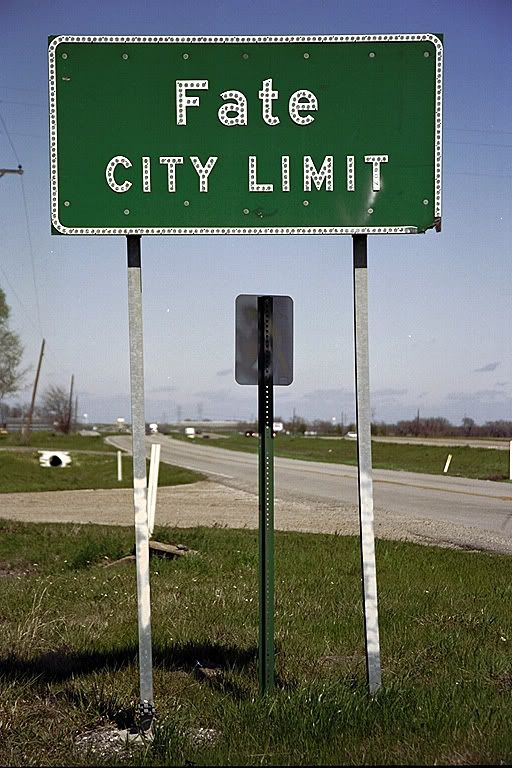

Tragic Flaws

Two summers ago, I read all of Greek tragedy for my comprehensive exams. Aside from making me incredibly depressed for a month, I realised something quite interesting: just about everything Aristotle says about tragic heroes is wrong. Aristotle had postulated the principle of the tragic flaw in tragedy. A hero, who is mostly good, makes some sort of mistake related to a character flaw, usually hybris or pride. However, from what I read, I realised that tragic heroes are almost never brought down by their flaws or by hybris. In fact, in most cases, the protagonist is actually destroyed by his or her virtues. In puzzling over this, I realised that Aristotle is, in fact, not trying to explain exactly what is happening in tragedy but what should be happening. He is answering a very specific challenge to the very existence of tragedy presented by Plato in the Republic Book III. Plato had argued that tragedy corrupted the audience. Aristotle's development of the tragic flaw is a response to this challenge.

Two summers ago, I read all of Greek tragedy for my comprehensive exams. Aside from making me incredibly depressed for a month, I realised something quite interesting: just about everything Aristotle says about tragic heroes is wrong. Aristotle had postulated the principle of the tragic flaw in tragedy. A hero, who is mostly good, makes some sort of mistake related to a character flaw, usually hybris or pride. However, from what I read, I realised that tragic heroes are almost never brought down by their flaws or by hybris. In fact, in most cases, the protagonist is actually destroyed by his or her virtues. In puzzling over this, I realised that Aristotle is, in fact, not trying to explain exactly what is happening in tragedy but what should be happening. He is answering a very specific challenge to the very existence of tragedy presented by Plato in the Republic Book III. Plato had argued that tragedy corrupted the audience. Aristotle's development of the tragic flaw is a response to this challenge.I will begin with an example. Even Oedipus Rex, the tragedy on which Aristotle focuses, does not seem to conform to Aristotle's model. Oedipus's downfall is the result of one of his own virtues, his keen intellect and wish to investigate. Oedipus had become king of Thebes by answering the riddle of the Sphinx. His success in becoming king of Thebes and his downfall in discovering his own origins are the result of the same character trait. Aristotle identifies this trait with hybris (as does the character Tiresias in the play itself), however, there is nothing clearly proud in Oedipus's desire to discover the origin of the plague in Thebes. Oedipus is referred to literally dozens of times in the play as wishing to "see" in various forms of the verb. This curiosity and intellect is not a vice. Yet it is this curiosity and intellect that destroys him, not hubris, and when he realises this, he takes out his own eyes so as never to see again.

Oedipus Rex was the example of a tragic flaw Aristotle himself used and even this example is not very clear. It is better to look at the Poetics as a response to a challenge to tragedy by Plato. Plato charges that tragedy corrupts people by showing good people being crushed. This is especially true in tragedy where they are often crushed because they are good. This teaches the audience that they should not bother being good. If they are good, it will not benefit them, and may in fact destroy them. An example of this would be Antigone, in which Antigone's love for her family and for the gods leads to her death and the death of her betrothed. This is an intractable problem for tragedy. If one wants to evoke fear and pity, one must a) show bad people whom we should not pity being crushed, or b) show good people who should not be crushed being crushed. Either of these corrupts the audience. a) corrupts them by causing them to identify with bad characters, and b) corrupts them by teaching them goodness is of no benefit.

Aristotle's solution, then, is the "tragic flaw". In the tragic flaw a character is mostly good, but has a specific flaw that destroys him or her. This provides an escape from Plato's criticism. The hero is still greater than most of the audience members. Therefore, the audience can and should feel pity for the hero on his or her downfall. However, the hero has a flaw that causes the hero to fail. Therefore, the audience feels an appropriate moral fear that badness leads to bad results. In this way, Aristotle has threaded the dilemma raised by Plato. The audience may feel both pity and fear, and neither of them will be corrupting. On the contrary, the emotions will help people sympathise with heroes better than themselves while fearing the negative consequences of wickedness.

As such, Aristotle's analysis in the Poetics is not an accurate description of what had happened in tragedy up to that point. Rather, it is a vision of how tragedy ought to function, a vision that has been largely successful through the influence of the Poetics. He is responding specifically to a charge by Plato in the Republic, that tragedy necessarily evokes either inappropriate pity or fear. Instead, Aristotle argues that tragedy can be morally edifying as well as pleasurable.