Prostitution and Just Price

I'd like to suggest an alternative solution to J.S. Mill's explanation of why we should not have the right to sell ourselves into slavery, and explain how this relates to issues like prostitution and surrogacy. J.S. Mill's explanation of why we ought not to have the right to sell ourselves into slavery is that, by exercising our freedom in this way, we would be unable to perform any other free acts. One cannot use one's freedom to annihilate one's freedom. This means freedom from slavery is an inalienable right.

I'd like to suggest an alternative solution to J.S. Mill's explanation of why we should not have the right to sell ourselves into slavery, and explain how this relates to issues like prostitution and surrogacy. J.S. Mill's explanation of why we ought not to have the right to sell ourselves into slavery is that, by exercising our freedom in this way, we would be unable to perform any other free acts. One cannot use one's freedom to annihilate one's freedom. This means freedom from slavery is an inalienable right.This seems a strong argument, but I'd like to suggest another one (there's nothing wrong with moral arguments being over-determined). Thomas Aquinas had a doctrine called "just price", which has largely been ignored since Adam Smith. This doctrine is that, though price is set largely by supply and demand, goods have a reasonable range for their value. This range is the range in which someone does not demand absurdly more or offer absurdly less relative to the effort and investment in the good in question. His concern was with the sale of food for exorbitant amounts during famine and similar cases. When people are charged substantially more or offered substantially less than the just price, it is only because there is a gross imbalance in power between buyer and seller. Such a sale or purchase would be exploitative and coersive, and should not even be legally binding.

Let us return then to slavery, prostitution and surrogacy. There are certain goods that are of infinite moral value. I will not depend this claim here. What I mean by infinite value is that it is incohent to compare these incommensurable goods against each other. Moreover, these goods of infinite value are of more valuable than any amount of any finite good. Among these goods are liberty, sexuality and procreation. Each of them is of infinite value, incommensurable with each other and of greater value than any amount of any finite good.

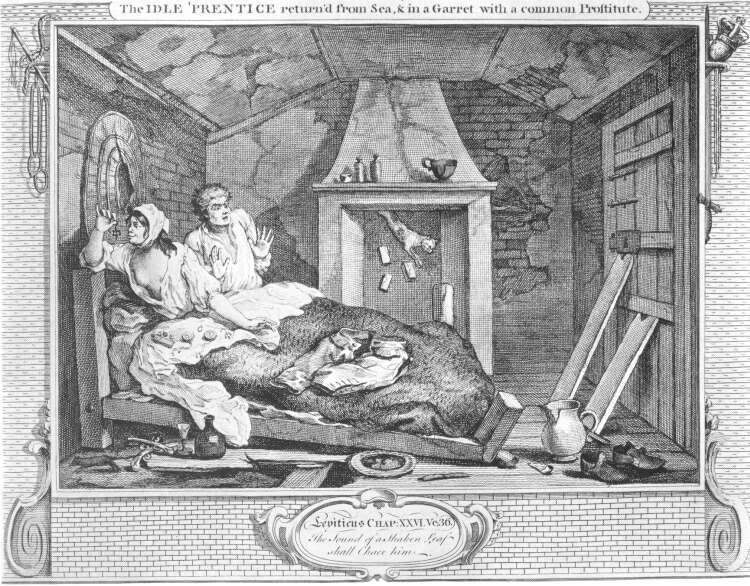

Therefore, when buys a slave or hires a prostitute or a surrogate, one is offering infinitely less in money for the value of the good being purchased. The difference is far worse than someone who offers a few loaves of bread for a house during a famine. Such a difference in price can only be exploitative and coercive. Usually, people who sell themselves as slaves, prostitutes or surrogates are in desperate need of money. When they are not, the buyer is still taking advantage of their ignorance of the value of their own liberty, sexuality or procreativity. Either way, the seller is being exploited by being given far less than just price.

This use of just price can be used to supplement J.S. Mill's argument against selling oneself into slavery. It has the possible disadvantage of requiring the idea of infinite value, but the advantage of being able to apply to obviously exploitative situations other than slavery.